There are two kinds of people in this world, those who believe there are two kinds of people and those who don’t. Black and white, on or off, all or nothing; all of these binary phrases characterise a dichotomous mindset (1). ‘Look…I’m an all or nothing kind of person’ is a common attitude amongst a high number of people in response to questions about diet and exercise. It’s as if they are waiting for a magical mixture of perfect timing, motivation and convenience in which to ‘start’ or go ‘on’ a diet and/or exercise program. On the face of it, this mindset may seem simple, clear cut and decisive, but is it playing havoc with their progress and long-term success?

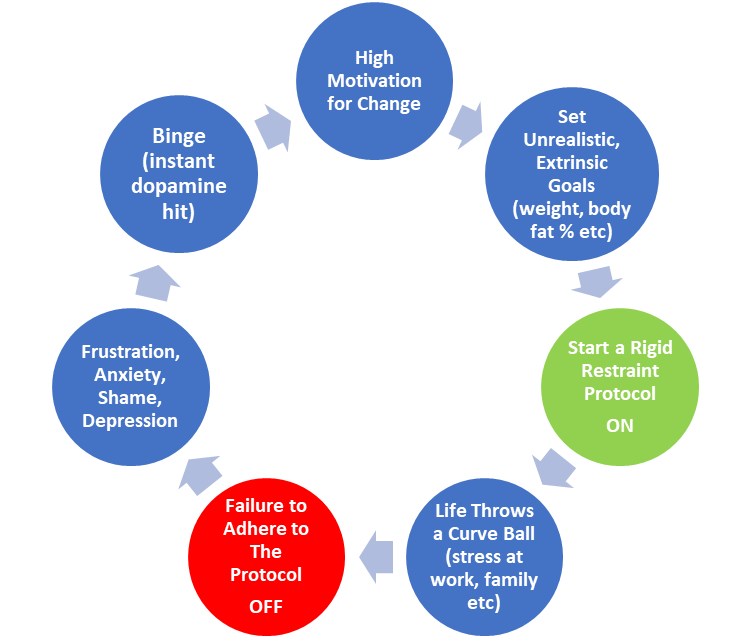

In health and fitness terms, a dichotomous mindset often manifests itself in bouts of high motivation for strict diet and/or rigorous exercise protocol, where unrealistic goals are set based on extrinsic feedback (weight, aesthetics, body fat % etc). It’s likely that the new rigid regime can’t be adhered to, due life getting in the way; family or work issues for example. Because this mindset only allows for one of two outcomes ‘success’ or ‘failure’, if adherence ceases, it is perceived as a failure. The initial high expectations for the new strict protocol soon turn into negative feelings such as frustration, shame and anxiety. To escape this negative state, short term satisfaction is often sought; sometimes in the form of a ‘binge’ from highly palatable ‘bad’ foods (2). Eventually, motivation to start up the strict dieting and/or intense exercise recurs as penance for bad behaviour, and the cycle repeats. Does this sound familiar?

Fig 1. The Vicious Cycle Infographic

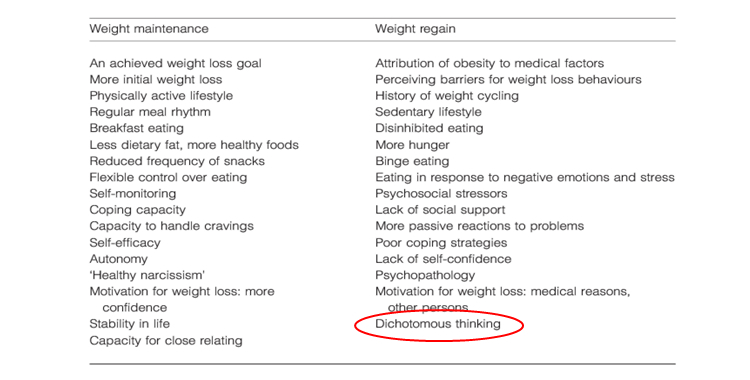

All diets require change, which will inevitably require some form of restraint. Restraint however, can be subcategorised two ways; rigid or flexible. Rigid restraint is defined as a dichotomous, ‘all-or-nothing’ approach to dieting, often demonising certain foods as ‘bad’. Flexible restraint is a less strict, ‘more or less’ approach to dieting where “fattening” foods can be eaten in limited quantities without guilt. Many studies (3,4,5&6) have correlated common themes observed in patients with both of these approaches;

This all or nothing approach is the antithesis of moderation, consistency and balance, which is often touted by health and fitness experts. It is a common theme amongst diet psychologists that the dichotomous mindset, which promotes rigid restraint, hinders long term success (13,14). In 2004, Byrne et al (7) revealed that dichotomous thinking was “one of the best prospective predictors of weight regain in obese people”. The notion that you must stick to rigid rules revolved around good and bad foods/behaviours ignores two key components of long term success; consistency and adherence. Diet and exercise need to flex with life’s ebb and flow. Tiggemen (9) noted that self-confessed strict dieters have more dysfunctional cognitive attitudes (including dichotomous thinking). According to Nguyen and Polivy (10) “individuals who consider themselves as successful dieters were more likely to be unrestrained (flexible) eaters than restraint (rigid) eaters”. Palascha et al (11) suggests “Such simplified and dysfunctional thinking styles should be avoided, since they have the potential to induce a rigid response to dietary transitions, and therefore impede people’s ability to maintain a healthy body weight”. Furthermore, in Elfhag and Rossner’s (12) conceptual review of success in weight loss maintenance, a dichotomous mindset is listed as a factor associated with weight regain;

This cycle isn’t all bad, there are periods of high motivation and action taken, we just need to take calculated steps which yield change that can be maintained. Avoiding these traps allows for gradual improvement, which builds into dramatic results.

So…don’t stress and take the first step today!